Born

to Run but Could Go Faster

By Paul

VanRaden

July

27, 2025

Topics

1)

Human

speed

2)

Animal

speed

3)

Bicycle

speed

4)

Angular

momentum

5)

Tumbling

6)

Sprint

flipping

7)

High

jumping

8)

Long

jumping

9)

Practicing,

testing, and winning

Introduction

Humans were

born to run but go much faster by riding a horse or bicycle or motorcycle or

automobile or bullet train or flying in an airplane or rocket ship. Many people

like to watch, play, practice, or compete in sports. More people can enjoy

simple sports that require less technology because often those sports cost less

but are still popular. To practice or compete in running, you need only shoes,

shorts, and a shirt. But after years of practice, sprinters today may go only

slightly faster than runners of previous generations because nobody has yet

found a faster way to run.

Gymnasts

compete indoors in several separate events held in small areas within a gym.

Their goals are to make many of the most difficult skills look easy, safe, and

precise. They use short bursts of speed to launch high into the air but cannot

win simply by being faster or jumping higher or farther than the others. Track

and field events have opposite goals, where style does not count at all.

Instead, winners just need to run fastest, jump highest, or jump farthest. Some

tumbling skills learned inside a gym such as repeated front flips or back flips

might help gymnasts win outside events because angular momentum could help

athletes go faster and jump higher or farther.

Human speed

Humans run

much slower than most animals because we balance upright and use 2 legs whereas

most other animals use all 4 legs. The fastest human sprinters have a top speed

of 43 kilometers per hour (kph) or 27 miles per

hour (mph) and a stride

about 4.3 meters (14 feet). Each step is about 2.2 meters (7 feet) ahead of the

last but using the other foot, so each foot touches down about every 4.4 meters

(14 feet). To go 100 meters in 10 seconds, the fastest runners take about 45

total steps 2.2 meters apart each taking 0.11 second. Thus, each leg takes

about 22 strides.

Each step of

a human sprinter launches them upward for 0.05 second before gravity brings

them back downward for the next 0.05 second. Their other leg then launches them

back upward but mostly forward. Gravity accelerates

or decelerates masses 9.8 meters (32 feet) per second squared, so the runner

only goes up and down about 2.5 cm (1 inch) calculated

as 9.8 * 0.052 * 100 = 2.5 or 32 * 0.052 = 0.08 feet

while traveling forward 2.2 meters (7 feet) with each step.

The fastest

way for humans to move forward without technology may be to preserve their

angular momentum like wheels do when rolling or gymnasts do when tumbling. In

the floor exercise, gymnasts train to maximize height or twists or difficulty

to get a high score. Instead, by retraining to maximize forward speed, some may

be able to tumble forward 100 meters in about 9 seconds. Their start may be a

little slower, but their top speed could be faster than running.

Animal speed

Kangaroos

use 2 legs but go 60% faster than humans by hopping and never trying to run

using one leg at a time. Kangaroos have top speed about 40 mph and a distance

per jump up to about 30 feet (10 meters), about 2.3 times longer than the

strides of human sprinters. Their legs have tendons that act as springs, like a

pogo

stick. Lemurs also hop upright on 2 legs when on the ground but mainly hop

from tree to tree. Birds have just 2 legs and most can fly by flapping their

feathered arms. An ostrich

uses the same running style as humans but can go 67% faster at 72 kph (45 mph)

and keep a fast pace for a long time.

Other

animals can run much faster using 4 legs and taking longer strides. Top speed

is about 97 kph (60 mph) for cheetahs and 64 kph (40 mph) for racehorses without a rider. Stride length is about 7 meters (21

feet) for cheetahs and 7.6 meters (25 feet) for racehorses. Horses have several

choices of how to run, called gaits.

They can walk, or trot (with left front and right rear legs forward and then

right front and left rear forward), or pace (with both left legs and then both

right legs forward), but gallop is the fastest with left front, right front

first (or vice versa) and then both rear legs pushing at the same time. A

galloping horse occasionally switches its lead leg when that leg gets tired. Rabbits

also run faster than humans using a gallop-like gait.

Other

primates such as chimpanzees can run a little faster than humans by using both

their arms and legs instead of just legs. When young, I noticed that most wild

animals and even our tame cows could outrun me, so I practiced running on hands

and feet when about 10 years old. My fastest style was a modified gallop

landing on right hand, then left, then right foot, then left, but with both

feet slightly to the left and both hands slightly to the right. That lets both

hands swing back further without hitting the groin or legs.

After my

hand got cut by a piece of metal in the lawn my parents told me to run upright

again. Shoes for the hands could have helped a lot. Foot shoes have flexible

soles and padding under the arch of your foot. Hand shoes would need more

internal support or padding that your hand could grasp because fingers do not

bend backward like toes do. Hands are not designed well for running which is

why some primates such as chimpanzees walk and run on their knuckles. Gorillas

also have longer arms and gallop by swinging both arms outside of their legs

but that style did not work for me.

Over short

distances, a human galloping using both arms and legs and taking longer strides

might reach or exceed the speed of sprinting on 2 legs with short strides, but

I have no math or evidence for that style, only imagination and some memory of

my experiments from around 1970. Humans may never know if this idea is possible

because few or no volunteers will spend the years of practicing and training to

build strength and optimize the methods. No coach can tell them how. Billions

of kids try to run fast before 1 of them grows up, trains hard, and breaks a

sprint record.

Bicycle speed

Bicycling

lets humans go twice as fast as running by transferring nearly all energy to

the rear wheel to push backward against the ground. Wheels roll with a stride

length of 0, preserve their angular momentum, and can coast forward using

little energy except that needed to push the air out of the way. When 1 part of

the wheel goes down, spokes lift the opposite side up and can almost fully

convert energy from the rider into forward momentum. Top sprint bikers can

average 6 seconds per 100 meters even while traveling 10 times farther than

sprint runners. They can go 1,000 meters in less than a minute compared to 2

minutes and 14 seconds for the fastest runner.

The human

body cannot be as efficient as a wheel, but feet, legs, and body spinning

forward in long, rotating flips should take less energy than pulling each leg

forward and back quickly with pure muscle power. Extra energy is required to

jump up, but your forward momentum could be preserved better by rotating

forward, like a wheel. Thousands

of years ago, people learned how to flip.

Angular momentum

Gymnasts,

trampolinists, ice skaters, and platform divers all contract their bodies into tight

tucks to spin fast. While doing front or back flips, a tumbler can travel

forward several meters. By conserving angular momentum, each jump can increase

forward speed like when pedaling a bicycle. That is why during floor exercise

the last jump in a tumbling pass is often the most impressive. With more floor

or track, speed could continue to increase until muscle fatigue, wind

resistance, drag from contact with the ground, or dizziness limit the progress.

A gymnast

may quickly decelerate into the last flip to transfer forward momentum into

upward momentum for more height and a fancier flip. Dismounts from high bar or

rings for men or uneven bar or balance beam for women also are often preceded

by gradually faster spins to store angular momentum. The stored circular

momentum then gets converted to upward momentum by releasing at the right time

to spend more time in the air. That same approach could be used in the high

jump if that sport lifts its ban on 2-feet takeoffs. Vaulters also convert

forward into upward momentum but with extra help from more technology: a small,

angled trampoline and a block to push off.

When

walking, human legs act like pendulums and have good

efficiency at the correct pace. A pendulum swings back and forth at a

steady pace requiring little energy to maintain momentum. Running is less

efficient because almost half of your energy is used to pull each leg forward

again to start a new stride. Your arms also swing in opposite directions not to

push you forward but to counteract the side-to-side twisting motion that your

leg and stomach muscles create.

When

running, your feet go up, forward, down, and backward in a somewhat circular

motion relative to your body, but your feet are not connected to each other.

Lowering your foot on one side does not lift the other like wheels or bike

pedals do and so your feet do not store angular momentum. Instead, muscles must

drive their movement. When running, your legs above the knee (thighs) still go

forward and backward somewhat like pendulums, but when going fast your legs

must be stopped and started by muscles rather than changing direction almost

freely by gravity as when walking at a slower, natural pace.

Tumbling

The sport of

tumbling uses a

25-meter track where athletes do 8 complex flips traveling only about 3 meters

forward each time but jumping very

high. Gymnasts do similar flips plus other acrobatic and dance moves across

a square floor of 12 meters on each side. That makes the diagonals about 17

meters across where the gymnasts first run quickly to generate speed, then

cartwheel or roundoff to convert forward speed into angular momentum, then use

the angular momentum to do about 3 complex flips. Both sports use spring-loaded

floors, but the floor exercise is more popular than tumbling in a straight

line.

A tumbler

must jump up to flip. Jumping only 0.3 meter (1 foot)

high gives you only 0.36 seconds to flip, going upward for 0.18 seconds and

downward for 0.18. The height is calculated as the gravitational constant

times the square of time which gives 10 meters * 0.182

= 0.3 meter high, or 32 feet * 0.182 = 1 foot high, with the

center of gravity moving in a parabola during the flip. Jumping up 0.6 meter (2

feet) gives the tumbler a half second to flip, going up for 0.25 seconds and

back down for 0.25, and jumping 0.9 meter (3 feet) high gives 0.64 seconds to

flip. The feet must be on the ground for some additional time to decelerate the

downward motion and accelerate back upward into the next jump, but that can be

as little as 10% of the air time based on this slow motion video.

The speed

limit for tumbling is less than for riding a bike because wheels have almost no

drag and no motion is wasted moving the biker s center of gravity up and down.

However, a biker s arm muscles get used very little whereas a tumbler generates

more power output per second by using arm, abdomen, back, and leg muscles

during each flip, both to contract into a tight ball at the top of the flip and

then to extend downward to meet the floor to start the next jump. Also, a

sprint bike weighs about 9 kg (20 pounds) that slows the athlete s start and

the time required to reach top speed.

Sprint flipping

To go 100

meters in 10 seconds, the tumbler could do 20 flips averaging 0.6 meters (2

feet) high and 5 meters (16.4 feet) forward per jump, taking a half second

each. With practice, 100 meters in 9 seconds may be possible by doing fewer

flips with more travel per flip such as 17 flips with 6-meter travel. Standing

vertical jumps can go up to 1.1 meters (44 inches) as measured for American

Football players, so 17-20 jumps in a row of 0.6 meters high may be possible.

The tumbler

s feet are briefly stationary at the start of each new flip, but the body and

center of gravity continue moving forward. Contracting into a ball brings both

feet quickly ahead in a continual circular motion to start each next flip. The

feet descend from higher than the athlete s height and slam onto the ground,

stopping much downward momentum of the legs but not forward progress of the

body. During a speed flip, the chest maintains near constant height, and the

head is going up when the feet come down. See Figure 1.

Flipping conserves the legs and whole body s angular momentum

but not as efficiently as a bicycle wheel. Better analogies for sprint flipping

may be a tire bouncing down a hill or a tightly inflated basketball, spinning

forward, and bouncing quickly, close to the floor. Sprint flipping would start

slower during the first few flips while gaining angular momentum but hopefully

with more top speed until the muscles tire. Handsprings make slow forward progress

due to laid out rather than tucked position and using arms half the time with

much weaker push than legs.

Gymnasts may

prefer back flips because they can see the ground before landing. While

flipping, your eyes will face forward, downward, backward, and upward every

half second regardless of front flipping or back flipping. Tumblers who can

land on a balance beam should be able to easily stay in their lane. Another

advantage of flipping is seeing how far ahead you are of the slower athletes,

whereas sprinters cannot easily look back.

Front flips

should be faster for sprint flipping where the goal is forward progress because

the posterior muscles that pull legs back are stronger than the stomach muscles

that pull legs forward. Runners accelerate quickly after the starting gun but

cannot decelerate quickly after the finish line because abdomen muscles are not

as strong as posterior muscles. For that same reason, running forward is also

faster than running backward.

High jumping

In high

jumping, nearly all athletes now use Dick Fosbury s upside-down

style instead of the face-down straddle style used until 1968. The Fosbury

style is not natural and requires more foam padding beyond the bar to avoid

breaking the neck when landing upside-down. Backflipping over the bar after a

quick tumbling setup (see Figure 2) might go even higher but was banned from

the sport s start more than a century ago. The highest legal jump was 2.45

meters (8 feet) in 1991.

All high

jumpers have been required to launch with just 1 foot which bans tumbling moves

that launch with both legs together. That rule s adoption and continuation

imply that two-foot takeoffs were a known advantage long ago and perhaps also

are today. Flips and 2-foot takeoffs were perhaps more dangerous back when

runners landed on sand instead of foam, but today that rule makes

little sense.

Backflip

high jumps, launching with both feet, should better convert forward momentum

into upward momentum, and using the larger posterior muscles more effectively

than front flipping. A disadvantage is not continuously seeing the bar, making

timing and spacing of the runup less accurate unless a grid or markers are

allowed in the runup area for targeting the takeoff.

Pole

vaulters go much higher. Another advantage of backflipping is that the body s

center of gravity needs less clearance over the bar by facing down and bending

forward at the waist instead of trying to bend backward like Fosbury.

Backflipping can also go feet first and slower over the bar using the same

elegant style as pole vaulting.

However, pole vaulters can easily see their bar the whole time, whereas

backflip high jumpers see their bar only after launching.

Long jumping

Long jumpers

convert about 20% of their 45 kph (27mph) forward momentum into upward momentum

during their last step or 2 on the 40-meter runup track. But your center of

gravity can descend almost a meter from your original height before you land

with feet ahead, on your posterior, leaning back. Thus, the long jump parabola

goes up by 0.3 meters in 0.18 seconds and then down by 1.3 meters for 0.37

seconds. The longest jump ever was 8.95 meters (29 feet) in 1991.

Long jumps

could also be longer by sprint flipping instead of sprint running before the

jump and launching with both feet together. Instead of leaning back and

extending your legs forward before landing, you could do about 7/8 of another

forward flip before landing, which may be easier and would look more natural

than the current style. In both long jump and high jump, takeoffs after

flipping will be less accurate compared to runners that are always facing

forward.

All 3 sports

- sprinting, high jumping, and long jumping - might need to consider new rules

or have separate divisions for tumbling style if the suggested methods work

well. Currently, the long jump allows 2-foot takeoffs and running contests

allow sprint flipping.

Practicing, testing, winning

Athletes

have good incentives to practice and win at official sports but little

incentive to develop new sports or methods. Can the ideas above be easily

tested? My best ideas for how to proceed are for athletes to:

1)

A

top speed faster than 43 kph or 27 mph would be needed to set records, but

slower speeds could win local contests. To be an improvement, an athlete s

sprint flip speed only needs to faster than that same athlete s running speed.

2)

Testing

sprint flip speed first on a springy tumbling track or gymnastic floor may be

safer than on a hard surface. Many cushions where the track or floor end could

provide a landing zone to catch the sprint flipper at top speed. Such tests

would require a radar gun or an excellent timing device.

3)

Flipping

in place is not a good test and takes more work than while moving because the

athlete preserves no angular momentum or spin. Instead, short bursts of flips on grass or on American football

field with carefully measured lines could help measure the distance traveled

per flip.

4)

Jump

up and down in place and touch a spot 0.6 meter (2 feet) above where you can

reach while standing. To sprint flip 100 meters, you may need to jump that high

about 20 times in a row.

5)

Record

the time needed per jump or per forward flip to verify the height and estimate

how much extra time is taken while your feet are on the ground and not in the

air.

6)

When

going fast but your legs are tired, learning how stop safely might require

quickly converting the last flip back into running motion so that you can use

different muscles to decelerate.

7)

Remember

that athletes who set world records started with much natural ability,

practiced the same skill for many years, and worked very hard to train their

muscles to go beyond what was previously possible. For example, workouts of Usain Bolt included sprinting while

pulling a sled of weights and sometimes throwing up from exhaustion.

Athletes can

compete in many sports. Swimmers race forward using free style, butterfly,

breaststroke, or backstroke but not doggie paddle. Track athletes race forward

by running or walking but not by running backward or crawling. If sprint

flipping is faster than running, separate events could still be restricted to

runners who use the slower, older, more natural one-leg-at-a-time style because

most people know how to run but not flip. Thus, many more people can

participate in running and start at younger ages.

Applying new

methods to old sports may take incentives, investment, and communication to get

useful results. The executive director of the US Trampoline and Tumbling

Association said she had never thought about maximizing forward speed. On their

own, each athlete might give up after a few tries. Prizes could be offered for

the best video demonstrations of tumbling methods applied to sprint or jump

events so that athletes could learn from each other s successes or failures. I

can post links to such attempts in this document.

The

probability that some athlete might be able to break the 100-meter running

record by sprint flipping may be 20%, but the probability that you can break

the record is much lower because your muscles may never perform like Usain Bolt

s highly trained muscles did. Probability of a long jump record may be 30%

because of speed plus a 2-foot takeoff should get more lift. The probability

that some athlete might backflip higher than the high jump record is maybe 50%

but will not set a record unless the rules change. My probability of breaking

any record is exactly 0 because I cannot do one flip and my 100-meter running

time in 2025 was 19 seconds, about half of Bolt s speed.

Happy

tumbling and enjoy your potential gold medal or world record in track and field

events. Please practice sprint flipping carefully using elbow and knee pads,

springy shoes, gloves, and helmet in case you crash. Do not blame me if you

injure yourself. I am 65 years old, not a tumbler, and not so foolish as to try

flipping forward 17 times in a row across 100 meters in 9 seconds. You decided

to try that, not me.

If you are a

good tumbler, in great shape, practice sprint tumbling a lot, and are convinced

that these ideas will not work please tell me so that I can advise others not

to try. If sprint tumbling works really well, you may want to keep it secret

until a major competition so that others do not copy and beat your new style or

change the rules before you get a chance to compete.

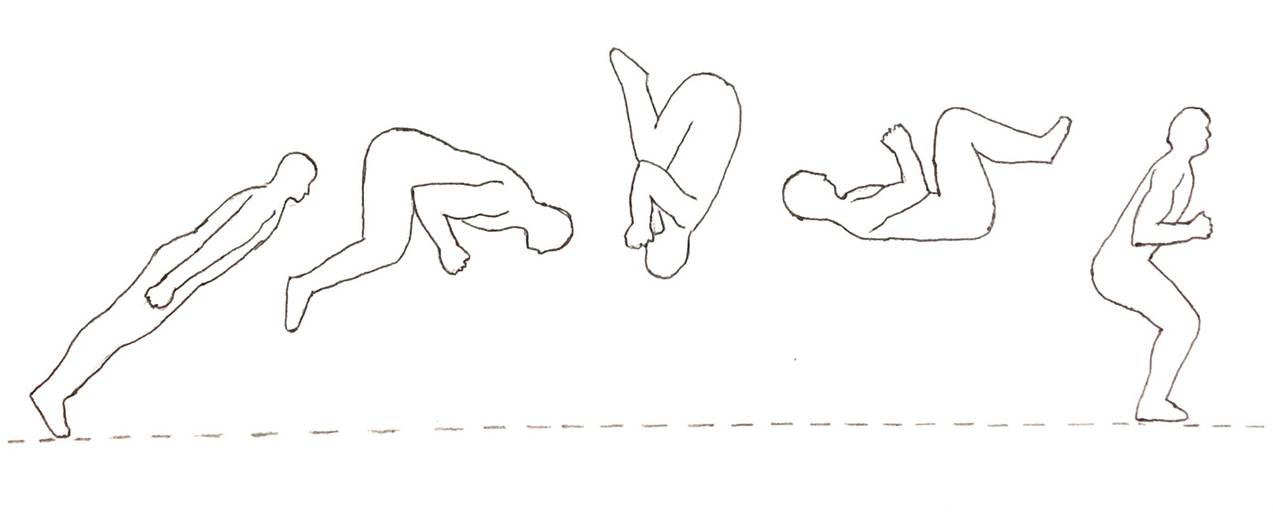

Figure 1.

One of the front flips (going left to right) needed to break the 100-meter

sprint record.

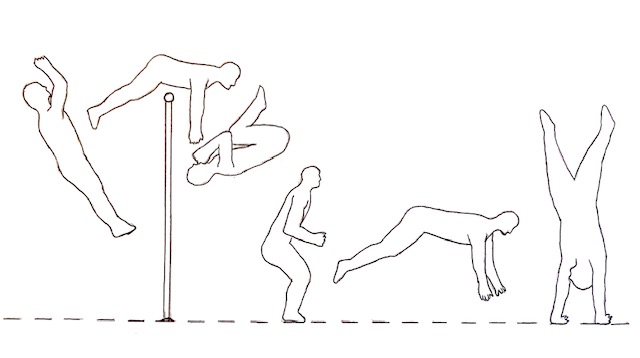

Figure 2. A

backflip attempt (going right to left) to win the high jump contest.

References

How

Fast Can A Human Run? (scienceabc.com)

Math

for Sprinters - Step Frequency and Stride Length (econathletes.com)

History of 100-meter sprint world records

How Fast Can A

Horse Run? - National Equine

How

Fast Can an Ostrich Run? (Everything Explained) | Birdfact

The

Science of Horse Racing: The Stride | TwinSpires

How

High (And Far) Can A Kangaroo Jump? - A-Z Animals (a-z-animals.com)

The

Speed of a Rabbit: How Fast Do They Run? | USA Rabbit Breeders

How

the Pogo Stick Leapt From Classic Toy to Extreme Sport | Smithsonian

(smithsonianmag.com)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_world_records_in_track_cycling

Arthur

D. Kuo, J. Maxwell Donelan, and Andy Ruina. 2005. Energetic

Effects of Walking Patterns Inverted Pendulum: Step-to-Step

Transitions.

Exercise and Sports Sciences Reviews 33:88-97.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tumbling_(sport)

Why aren't you allowed to jump off two feet in the high jump?

3 Ways To JUMP HIGHER

OFF TWO FEET

ALL GUYS WHO COULD DO TRIPLE BACKFLIP ON

GRASS

Men's

long jump world record progression - Wikipedia

Could

people do backflips/front flips in ancient times? : r/AskHistorians

Acrobatic

gymnastics in Greece from ancient times to the present day

Family

that walk on all fours have 'undone the last three million years of evolution'

(msn.com)

Born to Run - Bruce Springsteen

Walkin Man James Taylor [Born to

walk]

Back to: